Epistemic Status: High confidence, based on years studying the scientific literature on learning protocols and implementing them with concrete systems for personal use

Epistemic Effort: Medium, read through several papers, implemented the protocol for testing (daily usage since 2021)

Do you ever find yourself struggling to remember something important, whether it's for work, school, or just in your daily life? The solution might be simpler than you think: testing yourself.

Implementing active recall protocols can drastically improve your ability to remember information and perform better in any domain. In fact, I credit active recall with helping me turn a 3.2 GPA in chemical engineering into a 3.65 by the time I graduated, and I still use it to this day as a data scientist and graduate student. I have a vivid understanding of very technical information from graduate statistics I took a year ago. I could probably take those exams right now and ace them. It’s all because of the systems I built to invoke a concept I discovered in research literature… the testing effect.

In this post, I'll synthesize the research on studying methods, explain the active recall protocol, and provide insight on how to incorporate it into your learning workflow to maximize your memory retention and overall performance.

The Active Recall Principle

Active recall, also known as active retrieval, is the act of retrieving learned information. It can take many forms, such as explaining a concept, answering flashcard questions, or taking a practice test. In essence, all of these activities are executing the same cognitive function that constitutes the idea of active recall.

The fundamental principle of active recall is information retrieval from internal memory.

The easiest way to determine if a studying activity induces active recall is to ask the question, "Am I forced to remember information that I have encountered in the past?" If the answer is yes, then you are reaching into the depths of your memory and extracting information that was previously encoded.

Examples of common learning techniques that do not induce active retrieval are reading, reviewing notes, watching lectures, highlighting/underlining, and examining solutions to problem sets.

The Observer Effect In Learning

It was once assumed that learning took place at the initial encoding of information in the brain and that the act of remembering this knowledge did not contribute to the learning process. Psychologists have since learned that this belief is a fallacy.

In quantum field theory, there is a concept known as the observer effect, which describes the phenomenon that occurs when the act of observing a system changes the system. A parallel event occurs when we practice active recall, where the attempt to access knowledge from our biological memory changes the structures surrounding that memory.1

This touches on the concept of neuroplasticity, which is a property of the human brain that allows it to restructure synaptic connections in response to a stimulus. Joshua Foer uses the example of London cabbies in his book Moonwalking with Einstein to illustrate this point. Neuroscientist Eleanor Maguire examined the brains of cab drivers in London through MRI scans and discovered their right posterior hippocampus was abnormally large, which is an important region for spatial memory and navigation.2 A greater time spent as a cabbie correlated with a greater difference in size. The act of repeatedly recalling navigation information physically altered the brain circuits involved in spatial memory.

This notion of firing specific neural pathways as a means to enhancing those networks is also a reason why techniques leveraging deliberate practice are so effective. With deliberate practice, one focuses intensely on specific skills, thus activating those specific brain circuits and triggering neurobiological processes that strengthen those networks.

The cognitive challenge associated with remembering things learned in the past is believed to strengthen the neural pathways to those memories, resulting in an enhanced ability to recall that information in the future. So when it comes to optimizing the learning process, the practice of accessing knowledge should not be ignored. As Jeffrey Karpicke and Janell Blunt put it:

"Because each act of retrieval changes memory, the act of reconstructing knowledge must be considered essential to the process of learning."

Active retrieval is a means to cement our knowledge. The more instances we remember a fact or concept, the more likely we are to retain it in our long-term memory.

A Quick Literature Review of Studying Methods

The research on learning and memory has shed light on the effectiveness of active recall. The simple act of testing knowledge results in a phenomenon psychologists call the testing effect, which describes the remarkable improvement in learning produced by testing memory.34

A paper published in Science tested student learning using four different learning techniques: cram-studying (one-time review of text), repeated study (multiple reviews of text), concept mapping, and "retrieval practice" (alternating study and active recall). One week after the learning phase, students were asked to answer conceptual and inference questions (connect multiple concepts) testing their knowledge of the text. Retrieval practice was by far the most effective studying technique. Students that engaged in active recall correctly answered 67% of questions. In comparison, those who performed concept mapping answered 45% correctly (repeated study was a few percentage points higher) and the crammers answered less than 30% correctly. The other interesting result came from the students’ predictions of which techniques would yield the best results. Students thought the most effective techniques would be: 1) repeated study, 2) cram study, 3) concept mapping, and 4) retrieval practice. The most effective technique was active recall, yet the students predicted it would be the least effective.

This experiment offers insight into a broader problem in education surrounding a lack of understanding of how to learn. A similar set of results came from a study performed by Regan Gurung. He found that out of 11 studying options, college students rarely engaged in practice testing, yet this technique was one of the strongest predictors of exam performance.5 Instead, they most frequently read notes, read text, and used mnemonic devices to study for exams, which were all techniques concluded to be "low utility" by Dunlosky et al. in their monograph on learning techniques.6

Another study by Gurung on student studying behaviors also found active recall techniques like completing study guides, practice testing, and explaining problems to be the strongest predictors of high exam performance, whereas passive activities like highlighting text were predictors of low exam grades.7 Roediger and Karpicke drive this point home in their paper on memory testing:

"Taking a test on material can have a greater positive effect on future retention of that material than spending an equivalent amount of time restudying the material, even when performance on the test is far from perfect and no feedback is given on missed information."8

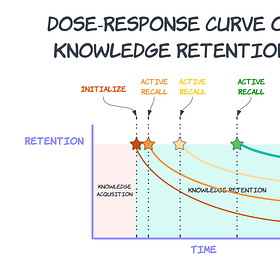

Research has also shown incredible improvements in information retention by combining active retrieval with spaced repetition,9 arguably the most powerful pair of techniques for long-term learning based on the evidence so far.

Implementing Active Recall

Once you have embraced the power of active recall, it actually becomes relatively easy to integrate it into your learning process. Any studying activities that force you to remember information is an instantiation of active recall. Common methods are practice testing, flashcards, writing, projects, and verbal explanation.

Evidence has shown a fusion of spaced repetition with active recall, i.e. spaced retrieval, to be the most powerful learning strategy, which I would agree with. The learning workflow depends on the content you are trying to learn, but every workflow should incorporate elements of active recall and spaced repetition.

Sönke Ahrens makes a great argument for integrating active recall with writing in his book How to Take Smart Notes. I believe a combination of spaced retrieval and active writing (restricting yourself to your personal knowledge to write about concepts and ideas) are excellent approaches for conceptual learning, whereas technical learning like computer programming is handled well by spaced retrieval, practice tests, and projects. I personally use a mixture of all of these techniques in my learning workflows.

Recap

Active recall is a powerful learning technique that involves retrieving knowledge from the brain

A vast body of experimental literature in the fields of learning and memory psychology supports active recall as one of the most effective strategies for cementing knowledge

The Knowledge Retention Algorithm

A literature review of spaced repetition and how to leverage this technique to systematically revisit acquired knowledge.

Building an Anki System for Life

In this post, I discuss how I use Anki as a retention tool for everything, my personal Anki configuration and workflow, the nuance of memorization versus understanding, and research literature studying the effectiveness of Anki.

References

J. D. Karpicke, J. R. Blunt. (2011). Retrieval Practice Produces More Learning than Elaborative Studying with Concept Mapping.

Joshua Foer. Moonwalking with Einstein, pg. 38

Henry L. Roediger, Jeffrey D. Karpicke. (2006). The Power of Testing Memory: Basic Research and Implications for Educational Practice.

Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006b). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17, 249–255

Regan A R Gurung. (2005). How Do Students Really Study (and Does It Matter)?

John Dunlosky, Katherine Rawson, Elizabeth Marsh, Mitchell Nathan, Daniel Willingham. (2013). Improving Students' Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology.

Regan A R Gurung, Janet Weidert, Amanda Jeske. (2010). Focusing on how students study.

Henry L. Roediger, Jeffrey D. Karpicke. (2006). The Power of Testing Memory: Basic Research and Implications for Educational Practice.

Jeffrey D. Karpicke, Althea Bauernschmidt. (2011). Spaced retrieval: Absolute spacing enhances learning regardless of relative spacing.

4:29 a.m. No quiero dormir, me resisto! Quiero vivir en este blog.